Animal prints that don't exist

Inspired experiments with Turing patterns

I’ve had a fascination lately with questions like: what makes something look alive? What is the visual language of the organic? There’s a sort of primitive, goopy, irregular pattern that evokes the feeling of growth, like bacteria in a petri dish. I wanted to know what it is about life that creates these patterns. Is there a geometry to life?

(Here’s an old Blender render of mine trying to approach the same question - not sure why I can’t add captions to videos on Substack.)

I experienced a strange closed loop sort of moment a few months ago. I was attending a Bjork dj set, staged under the Kosciuszko bridge in Brooklyn. The venue was enormous and packed - I think the whole event sold out within an hour - and from where I was standing I couldn’t see the stage, let alone Bjork herself. I surrendered to the sonic experience, which brought together sounds from around the world, mixing together left-field dance music with strange interludes of rhythmic laughing and unusual textures.

At some point during the sonic adventure I had an idea - what if I tried to procedurally code up animal prints that don’t exist?

I’m not sure what inspired (or maybe transmitted) the idea. But later, when researching the mathematics behind animal prints, I stumbled onto the work of a designer who was using similar growth algorithms to make masks for his client, Bjork!

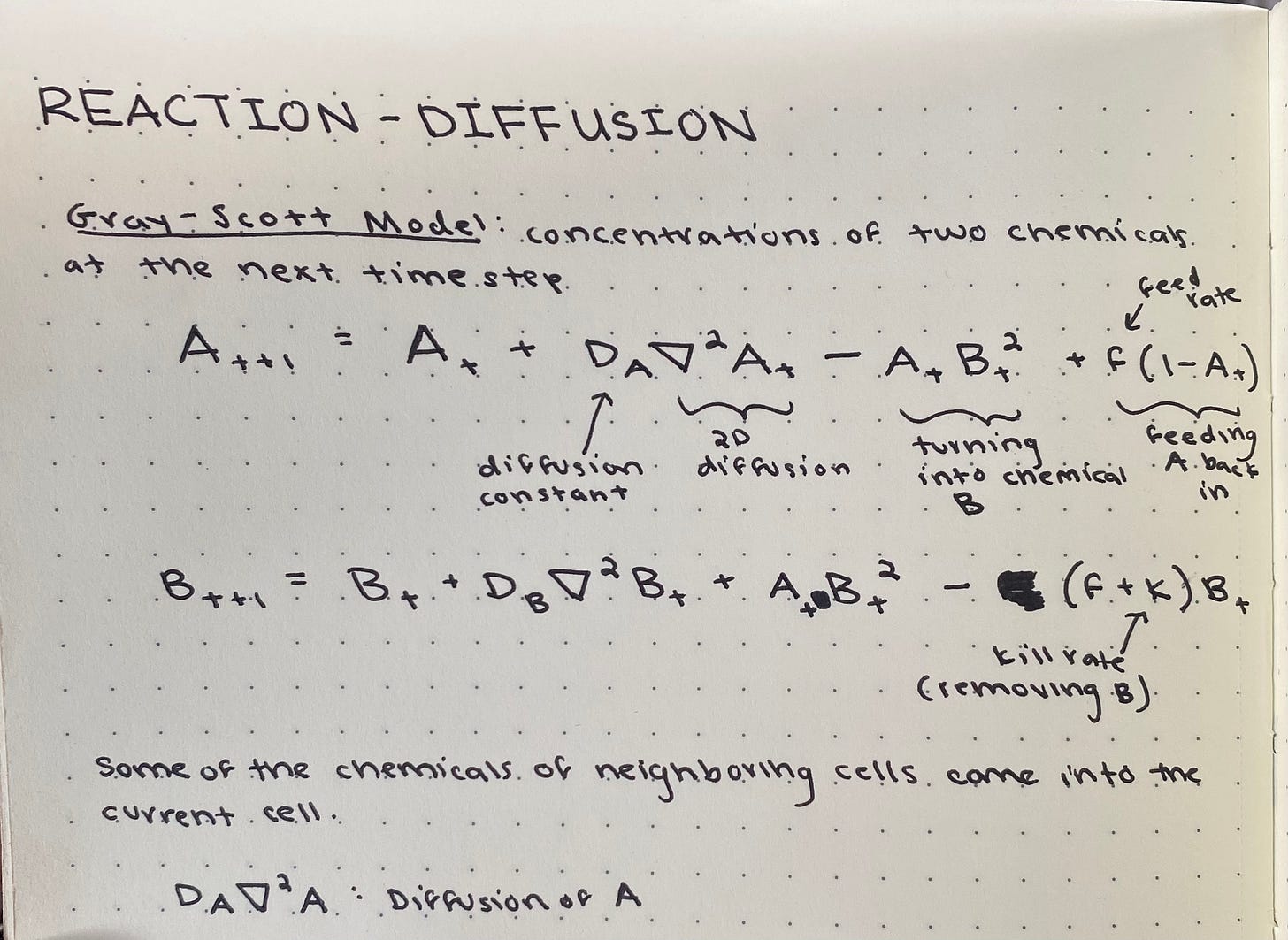

The math behind animal prints (and other generative naturally occurring patterns) was discovered by Alan Turing, as if inventing the computer wasn’t enough. The equations reveal that these patterns emerge out of a careful tension between two substances, perhaps two chemicals in a reaction. One acts as the reactor, pushing a reaction forward. The second is the inhibitor, slowing down the reaction. It’s this balance between this reaction and diffusion that creates the patterns we see on cheetahs and zebras. (If this sounds familiar, this sort of balancing act between push and pull is quite reminiscent of the nature of phase transitions, which I’ve written about in the past.)

I tried coding up a reaction-diffusion model in Unity to play with the resulting pattern generation. To do this, I used a compute shader. A compute shader is basically a shader (something that tells pixels what color to be) that does math. Each pixel performs the mathematical operations of the simulation, and the resulting color reveals the simulation output. This way, the simulation can be computed in parallel across the whole screen (on the GPU), rather than if-looping over one pixel at a time (on the CPU).

Here are some (preliminary) results:

It turns out the simple model of reaction-diffusion is a bit limited, but it’s a fun early exploration. I imagine this is something I will continue to refine and develop - I am fascinated by the idea of using the GPU to perform epic real time simulations. Parallel computing is exciting to me because it models how the real world works a bit better than usual computer programs do: networks of objects performing operations related to their neighboring objects, creating large scale patterns unknowable to the individual.